Boy Movies #19

How the internet turned The Social Network into a tragic gay text: an oral history

Some housekeeping: Because this issue of Boy Movies exceeds Gmail’s email size limits (the audacity to hit me and my gorgeous contributors with a character count…), be sure to either open it in a separate browser window or click “view entire message” at the bottom of the email. You can also read it directly on Substack. (This might honestly be the optimal way to do so since it makes accessing the footnotes easier, but do you!)

Fincher February: Week 4

When Jane Austen wrote “If I loved you less, I might be able to talk about it more,” she encapsulated the agony of overwhelming affection. That quote kept kicking around the recesses of my mind while putting together this issue centered around The Social Network, the David Fincher-directed, Aaron Sorkin-written adaptation of Ben Mezrich’s The Accidental Billionaires. I’ve been using the internet to declare my love for this film since I first saw it in October 2010; I’m still doing that, as recently as issue #18 of this newsletter. Honestly, giving myself an excuse to write about it was the entire inspiration behind Fincher February. And yet I had trouble sitting down to write an introduction to this, my long-threatened treatise on the boy movie that started it all (for me). What is there to say? Everything, nothing. If I loved The Social Network less, I might be able to talk about it more.

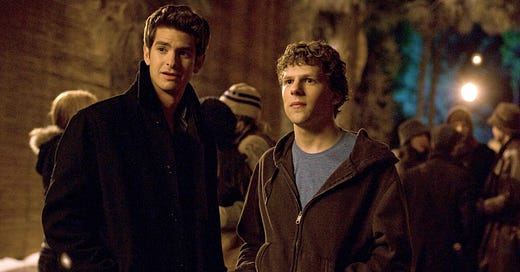

The Social Network isn’t a biopic of Mark Zuckerberg, nor is it a play-by-play of how Facebook got made. It’s not even necessarily an accurate portrait of what actually happened in that Harvard dorm room (as many of the major players depicted have stressed). The Social Network reframes the origins and legacy of Facebook within the context of emotional conflict. Sorkin said as much: “What attracted me to it had nothing to do with Facebook. The invention itself is as modern as it gets, but the story is as old as storytelling; the themes of friendship, loyalty, jealousy, class, and power.” Here, the biggest social media platform in the world is born during a night of “drunk, and angry, and stupid” blogging, after a nerd gets dumped by his girlfriend. A college kid with internet access getting put in his place by a woman he has no respect for is dangerous; Fincher would go on to explore the weaponization of male resentment in his post-Social Network works, like The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and Gone Girl. But it all started with Mark (Jesse Eisenberg) and Erica (Rooney Mara).

As I’ve aged, The Social Network has aged with me. My appreciation of its enduring relevance and the way it slyly examines how disrupting isn’t the same as rebuilding has grown substantially in the almost thirteen (kill me) years since its release — though it would be disingenuous to suggest that any of those things are what initially attracted me to it, or even that they’re what I initially think of when I reflect on it. To me, The Social Network is inseparable from the age I was when I saw it (literally fifteen), forever crystallizing it in my memory as a perfect work of art. To me, The Social Network is also about gay people. Let me explain.

I saw it for the first time in the same month of the same year that my dad died. I’ve written a bit about that before, the desperation spiral I found myself in. How do you find meaning in the wake of something so senseless? The Social Network became a lifeboat and an education; it was a boy movie that tapped into something relatable. It made the decay of a friendship feel visceral and tragic. It made me, for the first time, want to pay attention to things like color grading (all that yellow!), and a film’s score (Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross, thank you for your service), and unforgettable lines of dialogue (“If you guys were the inventors of Facebook, you’d have invented Facebook”). Suddenly, the names “David Fincher” and “Aaron Sorkin” meant something to me. I canonized them as visionaries. The internet, full of strangers who felt the same, only exacerbated their hero status1.

I distracted myself by feverishly posting about the cataclysmic, homoerotic, and utterly doomed bond between Mark and Eduardo Saverin (Andrew Garfield — my first exposure to him; it was like looking into the sun). I can think of few films more meaningful to me, and it’s difficult to overstate just how valuable it was to have something to throw myself into when I needed a reason to keep going. The glorious, demented Social Network fandom was a brightly burning, era-defining, culture-shifting (you wish I was kidding) time, poetic in its own way that a movie about the internet inspired the fervor it did online. One of my favorite things about embarking on this project was discovering how many participants mentioned having the exact same memories as others — it was true community theater, still unlike any other group that I’ve ever been part of.

To close out Fincher February, I went back to the early 2010s to put together an account of how The Social Network became a special kind of online phenomenon, as told by the people who were there in the trenches.

I. “When it was revealed to be a movie about Facebook I thought it was a joke.”

In July 2010, the full-length trailer for The Social Network — you know the one — was released and the world was never the same. No, really: There’s been plenty of writing2 on the use of that eerie cover of Radiohead’s “Creep,” but it’s difficult to overstate the work the trailer did in garnering wide interest for the film, which had been facing criticism and hand-wringing from the moment production was announced. “It was kind of getting beat up in the press,” Mark Woollen, who edited the trailer, told The New Yorker in 2019. “Like, ‘How can you make a movie about Facebook? Are you gonna make a movie about eBay or Amazon next?’” A lot of the marketing centered around how it wasn’t just a movie about Facebook, which worked well enough to get butts in seats. The film was released on October 1, 2010 and was immediately well-received, both critically and commercially, going on to make over 200 million dollars3.

Sarah Turbin (graphic designer, Boy Movies art director): I don’t remember which movie I was watching when the trailer for The Social Network came on. It might have been Inception. But I remember where I was sitting (near the front row) and where I was (in the movie theater next to my hometown). I was about to turn sixteen. I remember watching all the Facebook photos come in and out and wondering if it was a documentary, because the actors don’t appear until the middle of the trailer and all the photos are of normal people. And then when it was revealed to be a movie about Facebook I thought it was a joke.

Shirley Li (staff writer at The Atlantic): The trailer played before Inception and, I’m not kidding, for at least the first ten minutes of that movie I could not get that operatic cover of “Creep” out of my head. Hans Zimmer was bwaaahm-ing, but my mind was whisper-singing, “I want you to noooootice/when I’m not arouuuuund.”

Cassidy Olsen (writer, filmmaker): My first memory of seeing The Social Network was going to the AMC Seacourt (RIP) with you (Allison) and my mom. I do not remember if I had already seen Fight Club, but this was definitely the first Fincher I saw in a cinema. I was dipping my toe into being obsessed with movies around this time. The only movies I had loved as much before were franchise films, like Star Trek and Harry Potter and Lord of the Rings. I also remember seeing the trailer in advance and going, “This is one fucking cool trailer.”

Megan Vick (editor at TV Guide): I was an intern at Billboard when it came out so it was legitimately “the Justin Timberlake Facebook movie with the ‘Creep’ cover in the trailer.” I knew nothing else about it but everyone was talking about it. I was an unpaid intern at the time, so I had to wait for my dad to come to town to take me. Before we went my best friend messaged me, “There’s a British dude in it that I think is going to be your new fave.”

Daniel Taroy (head of social media at New York Magazine): Between the “Creep” cover and Justin Timberlake’s appearance, I remembering thinking the movie could end up being a fun mess.

Lucy (Tumblr user lucy-vanpelt): A close fandom friend that I’d made through Korean pop in the late aughts had been blogging on Tumblr and LiveJournal about The Social Network in October 2010 and I think I ended up downloading a super low quality version of the movie to watch on my laptop. I was in my freshman year of college at the time. I also vaguely recall normie friends talking about how good it was on Facebook (lol) and being like, “What? How good could a movie about Facebook be?” Famous last words…

Li: There must have been some Baader-Meinhof thing at play because I felt like I was constantly seeing stuff on it — billboards, headlines, GIFs, etc. What stands out in my memory is the cover of Entertainment Weekly. There were two versions: one with just Justin Timberlake because he was the biggest star, and another with him being flanked by Jesse Eisenberg and Andrew Garfield, with all three of them inexplicably looking in different directions. Someone left a copy of the latter in one of the common areas in my dorm, and I took it into my room and read the whole thing immediately. I was a fan of JT at the time, and I knew of Jesse’s work (partly because he went to my high school, go Bears), but I had no clue who Andrew was, and, look, I was nineteen, and I got very invested in cute actors back then.

Claire Cao (film editor at Big Issue Australia): All my early memories of The Social Network are inextricable from the mania of 2010s Tumblr — in fact, I think I literally saw GIFs and was like, “That hot guy looks like a baby deer” (Andrew Garfield, obviously). I was thirteen so I had no familiarity with Aaron Sorkin or The West Wing, but I was also an edgelord thirteen year old so I was obsessed with boy movies Fight Club and Se7en. I was immediately desperate to see it. I missed out on the theater run and ended up watching it via a pirated file that got passed around our grade on a hard-drive.

Aya Lehman (writer): I think I might have been the only person in America who saw that first trailer and thought, “Absolutely not.” I didn’t quite get it — I was sixsteen and trying to become a snob so I thought it was gauche to be making a film about Facebook so soon after its creation. I didn’t know who David Fincher was and was only familiar with Aaron Sorkin because my mom was obsessed with The West Wing, so it carried no cultural context for me. I finally caved and watched it on DVD in January 2011 just to finish all of the Best Picture nominees.

Lusi Zhang (fandom veteran): I went to BU and was a sophomore at the time. I originally had no interest in seeing it (a movie about the founding of Facebook? Boring!!!), but my suitemate at the time came back and said they dissed BU in the movie. I was like, “Well, now I have to see it to find out what they said about us.” I can literally still picture me sitting at my computer and her coming in to tell me about it so clearly.

II. “I was famously still straight when this movie came out.”

While Roger Ebert was busy describing David Fincher’s latest work as “cocksure” and “impatient,” a storm was brewing among young people online as the film, somewhat inexplicably, began to grow in popularity on blogging sites like Tumblr and LiveJournal (the same platform Mark spent the beginning of The Social Network drunk blogging the invention of Facemash on, mind you) in the weeks and months following its release in theaters. Online fandom had existed long before The Social Network — participants of this issue told me they’d been actively using the internet as early as 2002 — but this was something else entirely. For many, it was the first exposure to quote-unquote cinema they’d ever had. The fandom that sprung up around it was film Twitter before the existence of film Twitter.

Olsen: It immediately became a big part of my life. I think my brain understood that this was a real adult film, about adults, even though they’re mostly, like, nineteen, made by someone with passion and talent and control. I loved the score, which I think was maybe one of my earliest intros to electronic music, and the drama of it all.

Lucy Ford (culture writer): It sounds very silly to say now, but it felt like the first proper Film™️ that I’d ever seen. I didn’t grow up in a particularly filmy household and my friends weren’t filmy, so it wasn’t like I was sitting down to watch the greats regularly. This was my first introduction to Fincher, so it felt quite pivotal for that reason too. Also, because I’m me and I never met a boyband I didn’t love, I was just so happy to watch Justin Timberlake. I’m sorry, this was before we knew. But I remember being shocked and thrilled that he was actually a good actor?

Winnie Wang (writer, film programmer): I wasn’t a full fledged cinephile yet, so I didn’t know that films could be non-formulaic, thrilling without explosions, and speak to the digital generation in a non-condescending manner. The famous laptop smashing scene embedded itself into my brain and never left. It was truly exhilarating to discover David Fincher and Aaron Sorkin at age thirteen.

Li: That score! These performances! Those one-liners that are now tattooed in my brain! I remember feeling like I was being hit with a jolt of electricity over and over, scene by scene. The dialogue was so sharp, and the shots so dynamic, I couldn’t get enough of it. It’s a film that’s narratively dense, but there’s something so lyrical about it that it never feels laborious. It’s light on its feet.

Vick: I was awestruck by it. My original career plan had been to try and get a job at Rolling Stone and be Cameron Crowe a la Almost Famous, but The Social Network made me pivot and decide to move to LA after graduation to write a movie.

Turbin: The script resonated with me. I thought it was so clever and snappy. After watching The Social Network, I sought out Aaron Sorkin’s other work and became a big fan of The West Wing. His writing, for better or worse, has influenced every line of dialogue I’ve ever written since.

Cao: Like a lot of people, I was immediately obsessed with Sorkin’s trademark rapid-fire dialogue. I know his style gets roundly and deservedly mocked nowadays but it’s so perfect in this movie about douchey and grasping Harvard bros. The verbal parrying of the opening scene with Jesse Eisenberg and Rooney Mara remains incredible, and the film is just endlessly quotable in a way that I’m still dazzled by.

Shruthi Deivasigamani (fandom veteran): I think my immediate first instinct, as a junior in high school who lusted every day after the idea of college, was that I liked this movie because they lived in dreamy dorms on this elusive campus and I wanted to live in a dreamy dorm on that elusive campus.

Lucy: I was actually studying at Johns Hopkins where a lot of the movie was filmed, so that was one of the main hooks for me. I think I watched the movie October 21, 2010 — I have a Tumblr post timestamped around then lol-ing about being able to see Keyser Quad in the background of Mark walking back to “Kirkland House.”

Cao: It was one of those rare movies [where] you were left feeling like you’d watched a perfect movie. It felt so specific and keyed into that era of campus life, where being online is so entangled with the stakes of real life.

Lehman: The truth is I actually felt nothing for it the first time I watched it. I remember thinking it looked great, and I remember thinking Andrew Garfield looked great, so the next morning (before we had to return the DVD to Blockbuster) I watched the movie again with the commentary track featuring Jesse Eisenberg, Andrew Garfield, Justin Timberlake, Sorkin, Max Minghella, Armie Hammer, and Josh Pence (you know the one).

The way Andrew and Jesse talked about each other, talked about their characters, and talked about the way the story is so much more complex than just a retelling of the creation of Facebook really made me realize that I was watching a masterpiece. Within the next week I was reading the screenplay, watching the feature length documentary about the production, and screaming when the film won Best Drama at the Golden Globes (“inspiringly”).

Mary Alice Williams (writer of Commentary Mary): I relished in the morally ambiguous ending and the insane amount of cute boys that didn’t look like every “hot guy” we were exposed to in the previous decade. I remember feeling like, “Wow, I’m a cool person now because I get this movie.”

Zhang: To be completely honest, I thought Andrew was hot.

Taroy: I was famously still straight when this movie came out. Many things changed because of Andrew Garfield.

Vick: About ten minutes in, Andrew Russell Garfield showed up on screen, sat on a Harvard dorm desk, and said, “I’m here for you.” I have never been the same.

Li: I was especially enamored with his hair in the film (it’s so FULL and so SWOOSHY), and I spent a not insignificant amount of my down time my sophomore year reblogging photosets of him in which his coif looked especially good.

Wang: I recall desperately wanting to know the actor who played Eduardo Saverin and searching for his name in the credits because I thought he was cute. I frequently talked about a crush named “Andrew,” but there wasn’t anyone with that name so my friends suspected it was a celebrity. They searched the name on Google, hoping that autofill would betray me, but all that came up were U.S. presidents Andrew Jackson and Andrew Johnson.

Olsen: I think the rabidness and the hysteria of the fan base (girls and gays) was also born out of this being the first Andrew Garfield vehicle. He was a cute ass boy with floppy hair! I certainly had a huge crush on him.

Turbin: I was pretty bummed when I found out the real Eduardo Saverin wasn’t as charismatic as Andrew Garfield, nor was he a poor little meow meow. He remains a tax-evading kazillionaire who gave up his American citizenship to dodge the IRS.

Wang: I want to know exactly what was on the minds of Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross when they created the soundtrack names. [Song] titles [usually] make some kind of reference to the scene that the song plays during, but instead we get “Hand Covers Bruise,” “In Motion,” “A Familiar Taste,” “Intriguing Possibilities,” and, of course, “Penetration.”

Li: I’d seen enough of David Fincher’s filmography to know to brace myself for something psychologically disturbing and maybe even graphic. The film took me by surprise for how soft it felt, for lack of a better word. Beneath all the legal chatter and technobabble is a story of a friendship breakup, and I was very moved by Mark and Eduardo and that one shot of Andrew Garfield in the rain that I would go on to incessantly reblog on Tumblr.

Cao: Obviously the real thing that stuck with me was the heart of the movie, i.e. Jesse and Andrew’s insane heartbroken ex chemistry. “He was my best friend” followed by the shot of the empty chair will haunt me forever.

Olsen: Emotionally, I was obviously obsessed with the Mark and Eduardo relationship, but until I was in the trenches on Tumblr I don’t think I would have pointed you to that being why I liked it.

Williams: I remember scrolling Tumblr and reading everyone’s take on it and being pretty easily swept away.

Vick: I went mostly to understand what everyone was talking about at work and then ended up being a completely different person walking out of that theater.

III. “I would say it felt like we were collectively dropping acid for like three years.”

On paper, an adult drama about, yes, the creation of Facebook, but also the male hunger for power and boardroom betrayals, seemed like the Platonic ideal of an Oscar-baity boy movie, destined to be ignored by the rest of the general population. But it was that focus on power and betrayal that made it feel tailored to girls and gays in their teens and twenties who spent their free time hunting for GIFs of skinny boys exchanging emotionally charged glances. The Social Network is full of those, bolstered by Fincher’s nimble direction, Sorkin’s dialogue, and perhaps most importantly, the lived-in chemistry between Jesse Eisenberg and Andrew Garfield. A bedraggled Eduardo waiting in the rain in front of Mark’s door; his glassy-eyed shock when he learns Mark cut him out of the company; his unbridled, whole-bodied fury as he destroys Mark’s laptop in a final effort to make his former best friend understand the hurt he’s caused him — it was like catnip, and those who clued in first began preaching the good word online.

This was the very early 2010s, a few years before hopping on Twitter to chat about a piece of media you were obsessing over became the norm. In lieu of that, the fandom flourished on Tumblr and LiveJournal, ideal platforms for writing dissertations on the foreshadowing of Eduardo agreeing to “drop the ‘The’” (he was the ‘The’!) and for creators to share their impressively edited graphics. There was no risk of actors co-mingling with their stans, and people could recklessly post in peace. It’s no exaggeration to say that The Social Network helped usher in a new way of discussing movies online.

Here, The Social Network was a devastating, and devastatingly romantic, breakup movie. Here, The Social Network was a love story gone wrong, corrupted by money, by greed, by capitalism. It was important to discuss these facts with other like-minded individuals, as none of the critics who were getting paid to do so seemed to be taking notice. The actual Mark Zuckerberg and Eduardo Saverin were almost irrelevant4; it was the fictionalized versions of them that became symbols of gay duplicity. Even if you didn’t see the relationship that way upon first viewing, a quick scroll through your Tumblr dashboard could easily convince you otherwise. From 2010 through 2013 (“That ship did not sink quickly,” Olsen told me), unbridled mass hysteria spread across this corner of the internet like an infectious disease. The film was essential to building the fandom, but its long-term strength came from Eisenberg and Garfield themselves5, as Sony paraded them around for the seemingly endless press tour.

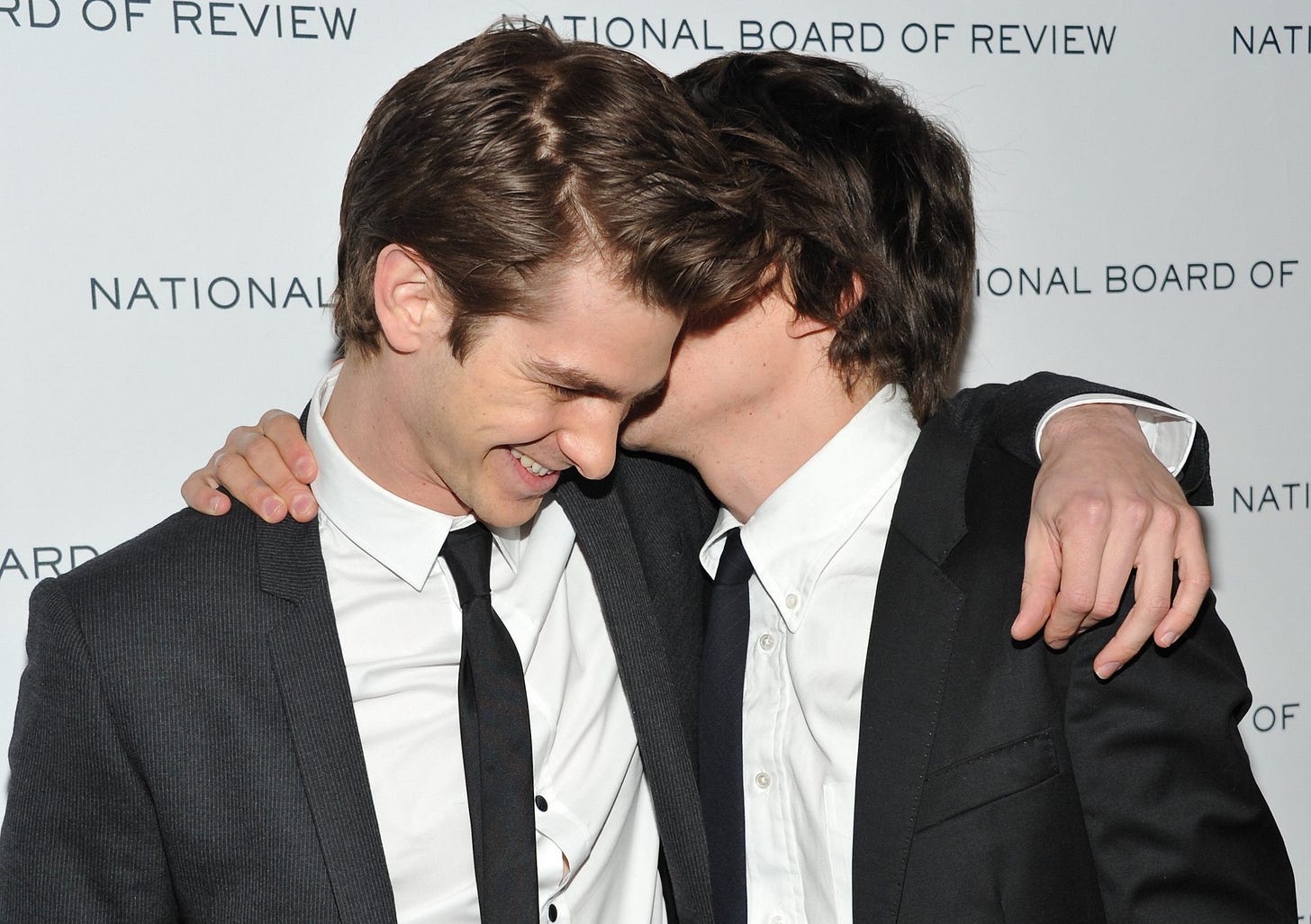

Because, as it turns out, they had chemistry off-screen, too: Garfield’s earnest, effusive affection for the drier Eisenberg came across unbearably sweet (“You didn’t know me at thirteen”/“I really wish I had6”). It’s taken less than Garfield’s proclamation that the film’s emotional core relied on him feeling like Eisenberg’s boyfriend7 to make the internet decide two actors were deeply in love, but we got that and more, and the narrative sure was captivating. Logging on meant voluntarily ingesting poison, but the poison came via GIFsets and bizarrely intimate interview clips — the kind of stuff that can’t be bleached out of a person’s brain. The poison tasted great. Most importantly, the poison helped foster a community.

During this time, you were as likely to encounter a GIF that trapped Garfield-as-Eduardo in an endless loop of his delivery of “fuck you flip-flops” as you were to stumble on a Tumblr post, typed in all caps, melting down over a story Garfield told8 on the DVD commentary about filming his side of a pivotal phone call between Mark and Eduardo while Eisenberg stood off-camera (“He kept on giving me these wonderful little ad-libs for me to react to … I think at one point I made him say: ‘I love you, you’re my best friend. Come, and we’ll get married, and we’ll live in a house together’”). Stories from set emerged to fuel the fire, like the one about Fincher directing Garfield to get Eisenberg in the right headspace for the laptop scene by hissing, “You’re a fucking dick and you betrayed your best fucking friend. Live with that,” in his face9.

There were champions of the fandom, like Tumblr users robin-sparkles and legendary GIF maker lawyerupasshole10. There were fan-created, and of course much happier, alternate endings. There was fanfiction, droves of it, as much about the characters of Mark and Eduardo as there was about Eisenberg and Garfield. We watched their every documented move, rapt, and responded accordingly: Why did Garfield put his finger in Eisenberg’s mouth that one time? We didn’t know for sure, but oh, did we speculate.

Li: I must confess I’m incredibly scared of what we’re about to discuss.

Lucy: TRULY, WHAT A TIME TO BE ALIVE.

Olsen: I would describe it as a fervent mosh pit of horny teen girls and gays who thought of Jesse Eisenberg and Andrew Garfield as their precious living toy dolls.

Zhang: I would say it felt like we were collectively dropping acid for like three years straight.

Turbin: Nobody but us would understand the collective psychosis that took root in all of our brains.

Williams: The Social Network really blew the fucking door off the hinges when it came to internet fandom.

Li: Please imagine me whispering this conspiratorially: It was the greatest place on Earth.

Taroy: What a horny time.

Lucy: I was like, “Okay, obviously Mark and Eduardo were in love with each other and had a horrible breakup,” and then I immediately started consuming the interviews Jesse and Andrew were doing for this movie and being like, “Wow, okay, these guys are clearly in love also? What’s that all about?”

Olsen: I specifically remember the photos of Jesse and Andrew in front of that white step and repeat where someone had edited the tiny background font to say “your gay can be seen from space11.”

Cao: I had pictures of them in Photoshopped flower crowns pasted to my high school folder for the world to see.

Wang: The people in the fandom were intense, perceptive, and creative. Through GIFs and analyses, I’d pick up on small details and who Fincher was as a filmmaker. There were jokes about how the cinematographer loved the color yellow, the use of the typeface Futura, and Mark’s Gap sweatshirt. I can’t recall another movie fandom other than Inception’s with the same degree of dedication and obsession.

Lehman: Aside from the excitement of collective fandom, it endures in my memory as a space outside of the traditionally cishet/white/male film community that allowed us to discuss and learn about filmmaking and film criticism in our own way without judgment.

Turbin: I remember endless GIFsets of the same scenes (the rain scene, Eduardo writing the algorithm on the window, the “lawyer up, asshole” scene, and the “you had one friend” scene come to mind), and the fun fact of David Fincher making Rooney Mara and Jesse reshoot the opening one hundred times. Yellow and blue. A poet named Richard Siken. And Euripides. (OF ALL THINGS… EURIPIDES. FOR REAL!!!)

Williams: The chokehold [Mumford & Sons’] “White Blank Page” had on us.

Wang: Also, Bon Iver’s “Skinny Love”?

Lucy: It seemed like every day from October 2010 through the Oscars the next year there was new official content and fan-generated content to be consumed. Every day there was some new devastating interview that Jesse or Andrew had given about how close they were. I was already primed to be receptive to RPF narratives, but that whole ride really cemented my reflexive reaction every time I see some homoerotic content on screen, which is to go and seek out the behind the scenes content and figure out if there are any good fic narratives there.

Vick: I can’t believe I am going on record with this, but I was there for the Social Network fanfics. There are two that I still think about regularly. Carry It in My Heart12, which was about Andrew and Jesse falling in love over the course of the movie. The second was one where Eduardo was never at Harvard but owned a bakery across from the Facebook offices after it was created, and he and Mark fall in love, and Mark learns Portuguese to tell him that. Both were impeccable works of art, but Carry It in My Heart ends with Andrew eating Nutella. I understand it wasn’t public knowledge he’s allergic to tree nuts when it was written, but it does take me out of it a bit.

Lehman: Sure, I read Carry It in My Heart like it was a religious text, what about it?

Zhang: I of course followed robin-sparkles, the iconic lawyerupasshole, and I randomly became friends with some of the other bigger blogs like thatwasnotveryravenofyou. Like everyone else, I read Carry It in My Heart (I was literally reading it on my iPod Touch at the time, sitting alone with my lunch in my school dining hall), and I remember that one comment fic in the kink meme13 which had a line that went something like, “You circumvent my heart.” (I’m sure someone else remembers this too but I couldn’t find it.) I read a ton of other things but these two stayed with me the most.

Lucy: The kink meme on Livejournal remains incredibly close to my heart. As for specific blogs, there was robin-sparkles, lawyerupasshole (all those GIFs, man), avid (professional Hollywood trailer wizard, now!). So many people that I met during that time that I still talk to regularly and have remained friends with after all these years. I still get Tumblr notifications from time to time on becoss, the Jesse Eisenberg quote blog a friend and I started.

Cao: I remember fandom icons lawyerupasshole, lucy-vanpelt/gdgdbaby (Lucy!!!), and robin-sparkles. Many of my friends now were people who I first came across reblogging, writing meta, and making edits of the film on Tumblr.

Wang: I remember Yuri, who went by the URL lawyerupasshole and was a rather prolific GIF maker, not just of scenes from The Social Network but Inception and other boy movies.

Cao: I printed out fanfiction of them at the local library. I watched all of Andrew Garfield's filmography (shout-out to Boy A and Red Riding!). SOMEONE EDITING THEIR COMMENTS INTO AN EHARMONY AD…

Williams: Honestly, my favorite thing of all time is the fake eHarmony commercial with Jesse and Andrew.

Lucy: I’ll never forget the eHarmony fanvideo.

Olsen: Anything went, posting was constant, and the lore was deep. It was a joyous and weird and funny time, particularly as it mixed, for many of us, with developing our own sense of selves in the real world.

Li: This is all deeply embarrassing to recount now, but I was so open online back then because Tumblr felt so, so safe. It seemed to me like everyone in the Social Network fandom was as enthusiastic as I was with all things Social Network, and people were wildly generous with their GIF-making and fanfic-writing, though I did not produce any content myself.

Cao: It was one of those really special fandoms where even if you weren’t creating content you felt like you were part of a very inclusive and passionate bubble that really enriched your experience of loving a film.

IV. “I had so much energy to feel angry about things back then.”

For films like The Social Network, press tours are precursors to awards season. Jesse Eisenberg spouting off one-liners about not having a Facebook but creating one “for a few weeks” under the alias of Andrew Garfield14 wasn’t just his unwitting way of making Tumblr users go crazy — it was all wrapped up in a larger promotional cycle. The studio was trying to woo the Academy (a body of voters who have not historically been swayed by Fincher’s meticulous style), while detracting critics like Slate’s Nathan Heller decried the filmmakers’ depiction of Harvard15. All the while, The Social Network’s secret weapon was its enthusiastic and insatiable legion of demographic-defying fans.

You have to imagine that if it were released today, Sony’s marketing team would have pandered exhaustingly to that legion. You can even envision a world where Garfield and Eisenberg would get accused of queerbaiting. (This was a simpler time, before the popularization of “queerbaiting.”) But the fact that the cast and crew gave no indication that they knew what was going on made it better16. It was with delirious passion that the fans devoured every interview, analyzed every word uttered by anyone involved with the making of the film, and engaged in battle with competing fandoms (the Social Network vs. Inception conflicts come to mind). Religiously keeping tabs on each awards show, from the Golden Globes to the SAGs to the BAFTAs to, of course, the Oscars, was a must, tallying up nominations and wins like they were personal achievements and refusing to let losses halt the momentum. Drinking the poison, you see, also meant enlisting in a war.

The biggest hit to the defending army was when Garfield didn’t manage to secure an Oscar nomination for his performance. The war was officially lost on February 27, 2011, at those cursed Academy Awards hosted by James Franco and Anne Hathaway, when The Social Network lost all but three of its eight nominations. Sorkin won Best Adapted Screenplay, but the film was absolutely decimated by Tom Hooper’s Academy-friendly period piece, The King’s Speech, which went on to win Best Picture. For many, it was the first Oscar ceremony they’d cared about, and the disappointment, after months of riding so high, was palpable.

Ford: This press tour changed my life. I’m being very serious.

Cao: I'm truly like [Oliver from Call Me By Your Name voice] “I remember everything” about that press tour.

Zhang: I couldn’t erase it from my mind if I tried!

Vick: I watched every interview on the internet about this movie during that press campaign. I remember all of the times Jesse said his mom used Facebook to connect with an old camp friend.

Cao: I’m embarrassed to admit this on a public forum but I was potentially way more invested in the press tour and Jesse and Andrew’s deranged comments about each other than the actual movie.

Ford: I think because I eventually went on to be someone who conducted interviews in press tours I now look back even more fondly on that run because I imagine what it would have been like to be getting these insanely intimate answers. Public male affection is so rare, and especially against the backdrop of this film that is incredibly sterile emotionally (rage, frustration, and hurt), the juxtaposition of the two makes it just *chef’s kiss*.

Turbin: I loved all the memes of Justin Timberlake just sitting there twiddling his thumbs while his co-stars did whatever it is that they were doing on that press tour.

Cao: Andrew saying he wished he knew Jesse when he was thirteen and that “a well of joy springs from [his] soul” every time he looks at him before following it up with, “You just remind me of a dog I once had.” When they presented at the VMAs and Justin Timberlake was somehow third-wheeling… I miss the era of celebrities and awards campaigns being unhinged and glamorous.

James Frankie Thomas (author of IDLEWILD): I was a latecomer to the fandom, so I didn’t see any of the press tour clips until years later, but I always found the “You didn’t know me at thirteen”/“I really wish I had” clip to be slightly overrated. To me, the apotheosis of that press tour was the Moviefone featurette17 in which Jesse Eisenberg mischievously asks, “How did you fall in love with me… on screen?” (“And off,” adds Justin Timberlake.) In response, Andrew Garfield, turning away shyly and chewing a fingernail, replies, “There’s something about your face that kind of, um, engenders a well of joy that springs from my soul,” and Jesse Eisenberg bites his lower lip to contain his smile. (Meanwhile, Justin Timberlake sits beside them in awkward silence, looking like he’d rather be anywhere else.)

Lucy: I’d never paid as much attention to awards season until then, and I probably won’t ever again, but we were all so ready for them to win all the awards. I remember holing up in my college dorm live streaming all the events on my laptop.

Lehman: I think in my almost thirteen years on Tumblr, I have only hit post limit one time and it was during awards season 2011. It was a dream.

Zhang: I had just come back from winter break when the Golden Globes happened, and I was visiting my friend in Miami before I had to go back to Boston. My friend did not care about any of this, so I was just sitting alone in her living room, in the dark, refreshing Tumblr for GIFs and updates because she didn’t have a TV. I don’t remember what I did last week but I do remember when Andrew Garfield tripped over the word “inspiringly” while introducing the film at the Golden Globes twelve years ago.

Wang: I certainly remember awards season where Andrew Garfield stumbled during the Golden Globes, trying his very best to say “inspiringly.”

Williams: I just remembered The Lift18 and I’m shaking.

Lucy: How angry we were when Andrew was snubbed for Best Supporting Actor [at the Oscars]. I had so much energy to feel angry about things back then.

Vick: I was more pissed that Andrew didn’t even get nominated for Best Supporting Actor but, wow, the audacity to give the Oscar to a movie about talking that year and it wasn’t the Sorkin movie.

Turbin: [The King’s Speech’s Best Picture win] was the first time I recognized that something that was okay but basically engineered to win an Oscar could bamboozle the Academy like that. The King’s Speech has all the big themes that would resonate more with them (World War II, a saccharine story about disability, feel-good moments, few morally gray characters). The people who voted for The King’s Speech over The Social Network underestimated the way the internet and social media would shape the next decade of our lives. It’s so indicative of all the old farts who made up the Academy then (and now, but maybe a little less), because how could they understand a movie like The Social Network?

Ford: When I think back to it now, it’s just so classic, isn’t it? There’s nothing awards shows love more than war and icy Britishness thawing. It’s a very obvious choice, which is why they made it. But I truly wonder if anyone has watched that film in the last decade.

Lucy: I was already angry enough that David Fincher didn’t win Best Director that I wrote this whole microfiction piece on Tumblr from his POV about how awards are stupid, if I remember correctly. I’m not going to go look for it now lest I melt into the ground from embarrassment, but it wasn’t great times in our corner of fandom on Tumblr, I’ll tell you that for free.

Lehman: Hell hath no fury like a girlie scorned. I actually think at this point, twelve years removed, I’m more upset about Fincher losing Best Director. Because now it’s actually sick that one of our greatest living auteurs lost to the guy who went on to direct (checks notes) Cats.

Cao: Has literally a single soul mentioned The King’s Speech since 2010? The most appalling upset in history. (Even worse than Crash winning over Brokeback Mountain, I'll say it!)

Li: It feels somewhat appropriate that The Social Network, a film about a guy who perpetually feels like an outsider, didn’t get punched to join the Oscar club.

Wang: The Academy is not a purveyor of taste and represents a narrow population of people, so I’m never too angry about losses. But it’s something I will never forget or forgive them for.

Zhang: I was livid. Of course Tom Hooper remains my enemy to this day.

Deivasigamani: Don’t talk to me about it.

Olsen: The King’s Speech sucks shit!!!!

V. “Boys don’t just like guns, fast cars, and hot girls; they enjoy formulas, algorithms and business deals from time to time as well.”

As I’ve made an exhaustive effort to prove during Fincher February, David Fincher is a boy director with girl movie sensibilities and an uncanny ability to harness crossover appeal. He’ll never be accused of being easy to work with19 — his predilection for doing hundreds of takes per scene and the things he demands from his cast and crew alone preclude him from that — but he’ll also never be accused of lacking a clear vision. The Social Network is a boy movie, yes. But the why of this particular boy movie is the more interesting story.

Wang: There are so many men in The Social Network! The film begins with a breakup, the severing of ties with a woman, propelling Mark to retreat into his dorm room to sulk and angrily blog in the presence of his roommate and, later, Eduardo. He meets other types of men too: bullish jocks, traitors (Sean’s the snake in there, Amy), level-headed entrepreneurs, sycophants.

Most interactions in the film are between men, even if the catalyst of these conversations and actions are a result of their complicated relationships with women, because David Fincher is interested in men and masculinity. There’s so much ambition, betrayal, rage, emotional restraint, and competition. When these themes aren’t literally manifested in the Winklevii’s physicality, they’re tied up in other forms like the ability to outwit, humiliate, accumulate capital, and inherit power.

Ford: Any woman who appears in the film is the worst person you’ve ever met. Just kidding, kind of. I understand that villainizing women is central to the whole plot, but I also would argue that probably went over a lot of boys’ heads at the time, the fact that Mark’s perception of women is unhealthy even if it did inadvertently breed the inception of social media. It’s also just bros making money, you know? Money is the central force — beyond friendship, loyalty, love. Money and power are deeply male concepts in film.

Li: I’d say it’s superficially a boy movie because it was marketed as the origin story of a very boy thing: building and running a company and making enemies along the way. There’s a lot of talk of VCs and shares and dilution of said shares — all stuff that I think, especially in pre-#girlboss 2010, wears the sheen of masculinity, if only because, well, men made up (and still make up) the bulk of C-suites. The ruthlessness of finance culture is the bread and butter of a subgenre of boy movies — your Wall Streets, your American Psychos, your Big Shorts. What they lack in big Fast and Furious-y explosions, they make up for in verbal fireworks!

Cao: The Social Network presents Mark’s masculinity as something pathetic and sad (left with billions of dollars and not one friend!), but it can’t help celebrating his disrupter folk hero narrative. It’s rooted in a college bro perspective — even as it mocks their insularity and how far they are up their own asses, it languishes in their scathing one-liners and shimmering genius. I mean, it reimagines Mark Zuckerberg as someone with breathtaking verbal wit, which, like, come on.

Wang: On a wider scale, The Social Network easily fits into the genre of math/tech films alongside Good Will Hunting, Moneyball, Steve Jobs, A Beautiful Mind, and The Imitation Game. Boys don’t just like guns, fast cars, and hot girls; they enjoy formulas, algorithms and business deals from time to time as well.

Olsen: It’s so funny, because it’s rabidly beloved by women, but a movie about a bunch of boys fighting over who gets to be cool and doing everything short of murdering each other to make it happen is always going to be a boy movie. It’s a movie about male friendship and love and insecurity, primarily, and the stuff about money and power and whatever comes last.

Lehman: On the surface, the combination of Aaron Sorkin and David Fincher could make any film [get] easily dismissed as a boy movie. There’s this annoying faux-feminism mindset of seeing any film that stars primarily men and immediately jumping to criticize it through the lens of “for a dollar, name a woman.” I can’t really speak for Aaron Sorkin because I don’t want to, but Fincher is a deeply misandrist filmmaker, so it’s honestly funny to me to be like, “Oh, this guy only makes movies about boys for boys,” and then it’s 120 minutes of Fincher emotionally destroying Mark Zuckerberg to the point that Zuckerberg probably legally could’ve sued for libel.

Li: I’d argue The Social Network is another David Fincher film that is secretly a girl movie, because, again, it’s about the dissolution of a relationship. Throughout the film, Mark is smarting from an ex calling him an asshole. Characters dealing with their relationship trauma, while getting involved in even more relationship drama? I’d say that’s pure, undiluted girl-movie fuel. Not only that, but this is a movie about reputation that pits establishment types against determined upstarts, set largely at a school. A lot of characters get mentioned in dialogue before we actually meet them; Mark and Eduardo talk extensively about Sean Parker long before JT swans into that restaurant. It’s Mean Girls-like, this examination of social hierarchies and individual likability.

Lucy: It makes me wonder if something that enhanced that connection for us was the fact that Andrew Garfield literally played it like a love story. He even said as much in the commentary and/or interviews during the press junket, how he had to “fall in love with Jesse” to make the whole dynamic work and for the feelings to come through the way they were intended to. Fandom loves to play with that kind of narrative, so when the actors are also buying into it there’s less of a “reach” in terms of romanticizing the story.

Taroy: The entire movie is a masterclass in gay treachery. To me, that’s a quintessential component of a boy movie.

Olsen: [The friendship angle] is something teens can relate to in a very literal sense, more so than perhaps any other themes or relationships Fincher explores elsewhere, or that were prominently featured in other films of this stature at the time. I know I didn’t really care as much about romantic relationships then because I hadn’t had them. We as young people got this movie with a core story about jealousy and friendship.

Li: Mark’s ambition, too, hit me hard, because of how much it was motivated by this fear of being overlooked. That was an insecurity that I understood to an extent; I’m no genius, far from it, but I was on a campus populated by thousands of striving undergrads like me, many of whom I was starting to realize were smarter than I could ever hope to be or more primed for success because of who they knew, or how they grew up. Plus, I was forming a lot of critical relationships at the time and attempting to navigate similar questions of who I wanted to be and whether these friendships were borne out of genuine care or of some twisted sense of competition. The fact that The Social Network was not just about college culture, but about wealth and class and identity and ego — all of that resonated to some degree.

Deivasigamani: An important detail in the movie is that Eduardo isn’t really suing Mark for money, he’s suing him because he was hurt by his friend who he loved and cared for. I don’t think of these as classic boy movie themes.

Olsen: The interest for me, and thus probably a lot of the other people like me on Tumblr at the time, was at the intersection of 1. Being excited that a movie was both Good and Cool, 2. Connecting with a core narrative I could relate to at that age, and 3. Being horny for boys.

Cao: Also, the intricate rituals of getting a wristy in a bathroom stall next to your best bro who is getting a blowjob in the adjacent stall… will I ever understand the bond between men?

Turbin: I also wonder if anyone who was stanning The Social Network online were the hot jocks of their schools… probably not.

VI. “David Fincher was in his Oracle at Delphi era when he made this film.”

The Social Network has been accused of letting Zuckerberg off easy20, and for the fact that it was made before Facebook really became an unstoppable global behemoth. But how were Fincher and Sorkin to know what would happen next? The election scandals, the fostering of neo-Nazis and conspiracy theories, Meta, that time Zuckerberg did whiteface while surfboarding, and the flagrancy with which Facebook has refused to own up to its role in it all — of course the uninhibited power of one company results in consequences for everyone, but in 2010, no one could’ve predicted what was coming. It’s incredible that a movie that isn’t really about Facebook, spearheaded by two people who don’t understand or have much interest in understanding the internet21, manages to grow in relevance with each year. The more distance we have from it, the more prescient it feels22.

Its historical implications are the most obvious salute to this, and you can throw a dart and hit a work that’s drawn inspiration from it (films like The Wolf of Wall Street, shows like Succession23, and of course Fincher’s own oeuvre). But the influence the film would have on the fans who spent years dedicating time and mental space to expressing their love for it online is also worth mentioning. Writers who honed their skills writing fanfiction have gone on to secure book deals. Lifelong friendships among people who met on the frontlines were solidified. The way many of us consume media was completely changed.

David Fincher and Aaron Sorkin could not have known what they were doing when they signed on to make this film. I would bet money that they did not set out to produce what became an honorary entry in the queer cinema canon. We were not the intended audience, but the most voracious audience we certainly became.

Lucy: It’s interesting, I don’t think I’ve rewatched the movie in several years and I’m almost afraid to because of everything that’s come out since then about IRL Mark Zuckerberg and Facebook/Meta, the way social media has in many ways informed and exacerbated the current political climate, not only in the U.S., but other parts of the world as well. Especially in the years following the 2016 election I’ve thought about that quite a bit. To be honest, though, I think the movie itself probably does still hold up as a piece of art, and from the lens of a content creator/fic writer, we were always writing about fictional versions of real people, anyway.

Olsen: It’s a precisely written, evocatively directed, and wonderfully performed bit of biographical fiction, which introduced the world to some phenomenal talent, at least one canceled guy, and the idea of Justin Timberlake as an actor. I would still call it my favorite of Fincher’s films and one of my favorite films of the 2010s.

Li: It was the perfect pairing of creative minds, and it is endlessly rewatchable because it is relentlessly excited by its subject and gleeful about every turn in the story. Take, for instance, the scene of the Winklevii going to meet with the president of Harvard: Before they enter, the camera only films them from the neck down; they’re already chickens running around with their heads cut off, even if they don’t know it yet. The editing is incredible, so fleet-footed and well-paced for a movie that must cover two lawsuits at the same time.

Thomas: I do believe, to my own surprise, that time has only improved the film. It’s served so well by the dramatic irony of our knowledge of what would later become of Facebook and Zuckerberg.

Lehman: Fincher and Sorkin literally said, “Look, this guy is an asshole with unchecked power and he feels no remorse whatsoever for his behavior.” And then like five years later, Facebook destabilized democracy in America. 2009 David Fincher was in his Oracle at Delphi era when he made this film.

Ford: I think it holds up very well, especially considering it was a biopic about something incredibly recent. That now feels very omnipresent, as everything has to be based on a true story, but it was thrilling to almost get a peak behind a curtain that had only just closed.

Cao: The film is obviously a time capsule — the internet is vastly different now, and it’s interesting seeing Facebook’s origins as an exclusive, cool, and campus-based phenomenon. It’s kind of tragic how uncool the platform is now, but despite being dated in that sense, the film itself remains so slick for bringing together all these creatives who were at the top of their game.

Wang: The digital world was moving so quickly that by the time the film came out, Napster and Myspace were appropriately dated. In some ways, it’s incredible that Fincher knew to make this film in 2010, centering on the destruction and harm that surrounds Facebook’s operation right before we learned about U.S. election interference and its role in perpetuating genocide in Myanmar.

Turbin: The power Facebook has perturbs me. The deep irony of a website that was made to make us feel more connected to one another doing the exact opposite! The moral unease I feel about using Facebook (and Instagram, for that matter) were all foreshadowed in The Social Network. Neither Shakespeare nor Asimov could have concocted this.

When the movie came out, Facebook rented out theaters so their employees could watch it together. If someone made a movie about how deeply flawed I was, I don’t think I’d show it to my employees. Maybe [Zuckerberg] thought the movie portrayed him sympathetically. Eisenberg does such a good job of making him seem human and you understand his motives by the end. But it’s certainly not a movie that flatters him. That gives me some insight into what kind of person the real Zuckerberg is.

Deivasigamani: In the context of what Facebook has become, it’s almost eerie because Mark Zuckerberg is so much more evil than we could have imagined in 2010.

Li: Watching it remains a powerful experience because it so carefully tracked the fallout of Facebook’s development, not the 1s and 0s that brought it to digital life. The story’s just so juicy. Sure, it’s about how a dork who wore slides around campus ended up founding a billion-dollar company, but the questions it poses still resonate today: Why are we so drawn to apparent geniuses and self-styled visionaries? What is the internet doing to us — connecting us, or flattening us? Who do we become when we chase success, and perhaps more important, when we achieve it? It’s no wonder we’re still getting so many projects about Silicon Valley; they’re all creation myths in their own ways, and we’re still wrestling with the consequences of glamorizing so many ideas so quickly.

Olsen: If anything, the only criticism I have of the film now is that it was much too kind to Facebook. It’s almost quaint in its depiction of “the social network.” Of course no one could have known what the company would become between 2010 to 2020, what kind of atrocities and human rights violations would happen as a result of their policies and greed, but the focus of the film is so, so far away from what I would want to say about Facebook now. If you treat it as fiction, however, it’s essentially perfect.

Taroy: Obviously I don’t think anyone could've anticipated the scale of Facebook and Zuckerberg’s bad behavior, especially in our post-fake news world. However, the film itself is less about the platform itself than it is about betrayal, fraught relationships, and the aforementioned gay treachery. That, coupled with very strong and under-rewarded performances (and a perfect score), is what makes it so timeless.

Li: It is not a factual rendering of the founding of Facebook, but an examination of its emotional baggage. The first line out of Mark’s mouth when we flash forward to the courtroom is, “That’s not what happened.” The scenes themselves may not be true, but these feelings — the elation of success, the pain of betrayal — certainly are. Which is why, I think, the downbeat, minor-key ending that’s focused on Mark’s regret and ache is all the more powerful, especially now that we’re more than a decade removed from it.

Thomas: In 2010, the film would have read as an ambiguous success story, a tale of a young man who achieved fame and fortune at great personal cost; today, knowing how world-historically evil this young man would grow up to be, the story plays as tragedy. The tragic element also deepens the character of Eduardo Saverin, who’s a bit of a chump as written, but now reads as a man unknowingly in thrall to a monster. It interestingly complicates the ending to know that the heartbroken Eduardo actually dodged a huge bullet.

Cao: I find it even more rewarding upon recent rewatch, maybe because I first watched it as a teenager and missed out on a lot of nuance. At its core, the film is about a tragic friendship breakdown that the fictional Eduardo feels absolutely blindsided by, something that resonates more with me now.

I feel like The Social Network resonates so strongly with the girls and the gays because it’s unashamed about the tenderness and vulnerability of friendship. This movie is so grounded in petty jealousies, regret, and insecurity — it’s not really about Facebook at all, but about Eduardo flying to California in a rainstorm and turning up at Mark’s door like a pathetic wet dog because he realizes his best friend suddenly stopped being his best friend in a way he can’t control nor help. It’s about Mark realizing the full extent of the way he mistreated the person closest to him, about the build up of minuscule cruelties and fuck-ups in any close friendship. It lives in the emotional passages where Eduardo and Sean Parker are possessively bitching over a horrible little nerd. It’s so grandly dramatic, and wears its heart on its sleeve.

Li: Thinking about this reminds me of the question of whether it’s time to do another movie about Facebook, a sequel to The Social Network. Sorkin’s talked about doing it if Fincher’s in, and I agree that it’d be an interesting exercise, but I don’t know if it’d be as potent as what they’ve already made. Watching The Social Network still breaks my heart because its conflicts are specific to its characters, and the emotions being tracked — resentment, jealousy, pride — are informed by these people’s youth and the setting they find themselves in.

I’d be curious what a Sorkin script about Facebook’s security and disinformation woes would be like, and what Fincher would do with that, but The Social Network works so well because its focus is actually smaller than you expect. You go in thinking you’re getting a history lesson, but you end up with a perceptive portrait of one character. It’d be hard to pull off that trick again.

Vick: I still watch it once every three months.

Taroy: I’ll never forgive Armie Hammer for robbing me of a comprehensive oral history of The Social Network. That being said, I need a Banshees-style reunion between Jesse and Andrew (Justin can stay in the woods).

Lucy: If anything, I’m grateful to the movie for the way it helped me connect with other fans and build lasting friendships.

Williams: Probably my latest in life moment that made me say culture is for me. Crazy that I’m still friends with some of the same people from back then.

Lucy: It really was such a fun time to be on Tumblr and LiveJournal — with over a decade of distance, I still miss the way fandom communities operated before the bite-sized (and video) form really took over mainstream social media.

Zhang: This movie truly altered my brain chemistry and the trajectory of my life. It’s really a case of “you had to be there.”

Ford: There’s just nothing better than when a film’s memeability is as good as the film itself. Usually it’s one or the other, and I think it’s beautiful kismet that a film about the internet at a very specific time, an internet that doesn’t exist anymore, still has such a life on the internet today.

All graphics by Sarah Turbin. Additional editing by Ariana Bacle.

I want to be very clear that I 1. was a teen, and 2. no longer consider Aaron Sorkin a hero.

In 2019, The New Yorker did in fact blame it for the boom of covers of classic songs in movie trailers, an affliction our culture still suffers from.

I mostly mention this because it literally would never happen today.

“Whether the real Mark Zuckerberg went through this is not something I’m concerned about," as Turbin put it.

I’m not sure I can even print the nickname the Eisenberg-Garfield duo was (at the time, affectionately) given without, like, losing my job, but it sounds like “unicorn” and if you know, you know.

Absolutely changed the world. Also, lmfao at the title of this video.

“As soon as I met him, I fell in love with him,” Garfield said in an interview. “I had to support him and support his genius, and be protective of him, and want him to myself. To be his boyfriend, really.”

Aya Lehman wrote an exceptional piece that discusses this moment and more!

lawyerupasshole was never deleted but has long since gone dormant! They presumably never saw my Tumblr message requesting a comment from them for this issue and left no other method of contact. lawyerupasshole, if this ever makes it way to you, thank you for everything.

I tried so hard to find this image and could not, but if anyone happens to track it down please send it my way.

Look, I won’t dox the identity of the person who wrote Carry It in My Heart, but I will say they are now pretty well-known in their own regard and did not return my request for comment. I will also say I followed updates on this fanfic in my sophomore year of high school like it was Great Expectations. I have memories of reading it on my iPod Touch under a desk in Spanish class.

Kink memes were big interactive LiveJournal posts in which people would post ideas for fanfiction they wanted to read and writers would fulfill requests in the comments. Community theater!

“I don’t have a Facebook page but I set one up under an alias, as Andrew Garfield, for a few weeks and made no friends,” Eisenberg said at the film’s UK premiere. “No one was interested, except Andrew’s alias who wanted to be best friends with his own fan page.”

So funny that this movie had its own version of “it’s a culture, not a costume” discourse.

As Li puts it, “Internet fandom in the early 2010s had a markedly different tone from what it is today, and I think part of that was because Tumblr encouraged appreciation of the work, not total obsession with a celebrity’s personal life. At least, despite the stuff on Andrew and Jesse, I never felt like folks were going too far into parasocial territory with them, or with internet boyfriends overall, whether it was Andrew Garfield or Tom Hiddleston or Idris Elba. There were maybe a handful of slightly creepy posts, but in general, it was rather innocent and just, like, earnest and silly at most.”

I still don’t know what was going on in the Moviefone featurette. Timberlake’s complete silence… the look on his face…

In reference, of course, to the time-stopping moment at the 2011 Golden Globes when Eisenberg lifted Garfield out of his seat on his way to the stage after The Social Network won Best Drama. Producer Scott Rudin (ew) referred to them as the film’s “extraordinary right brain, left brain combination.”

In 2015, Vanity Fair published a piece titled, “David Fincher’s Most-Used Phrase on Set: ‘Shut the F---- Up, Please.”

It should be noted that when it was first released, many critics saw it as too hard on Zuckerberg. For New York Magazine, Mark Harris wrote, “It’s one thing to play with Tony Blair or Bill Clinton. It’s a new kind of license to turn a real-life 26-year-old whose most life-changing decisions were made as a teenager into an incarnation of Silicon Valley killer instinct.” Funnily enough, Sorkin eventually heaped praise on Zuckerberg in his Golden Globes speech, calling him “a great entrepreneur, a visionary, and an incredible altruist.” Lol!

Of Sorkin’s ignorance, Lawrence Lessig of The New Republic wrote, “This is like a film about the atomic bomb which never even introduces the idea that an explosion produced through atomic fission is importantly different from an explosion produced by dynamite.”

A selection of moments that did not age well, according to participants of this issue:

Vick: I mean, Sorkin hates women.

Li: There’s, of course, the people involved: Scott Rudin and Kevin Spacey are both producers, and their reputations have cratered in the intervening years. The idea of two Armie Hammers on screen doesn’t sound so enticing today.

Williams: Armie Hammer… c’est la vie.

Wang: What doesn’t hold up today? Max Minghella playing an Indian character. Sorkin writing dialogue about how Asian girls are attracted to Eduardo and that they can’t dance. The transphobic slur used in the scene where Erica discovers Mark’s blog.

Turbin: Casting Max Minghella to play Divya Narendra is pretty bad.

Li: I did also cringe a bit in my rewatch at the film’s portrayal of Asian women. It’s funny; I wasn’t so sensitive to this at nineteen, and I’d need a whole separate questionnaire to get into the reasons why. But now, hearing the dialogue ogling Asian women and seeing Brenda Song’s arc amount to “crazy girlfriend” stings a bit. I know, I know: The film’s way harsher on Mark’s fragile masculinity than it is on people who look like me, but the fact remains that this was, as far as I remember, one of the few times I saw an Asian American woman my age on screen, and the logic of her characterization seeped into my reality — or my understanding of my reality. In the years since the film’s release, I think there’s been a lot of great discussion on the way Hollywood puts underrepresented folks into boxes, and I’d be curious if Sorkin would write the same scenes now.

I can’t let this newsletter end without giving special mention to this galaxy-brained take by playwright, film tutor, and critic, Ivana Brehas: “The emotionally-charged relationship between Succession’s Kendall and Stewy reminds me of The Social Network at times. (“I was your only friend. You had one friend.” / “You're my third-oldest friend and you fucked me like a tied goat.”) The lesson: fictional men will literally have toxic gay business-friendships with their one and only boy best friend.”

This is more Fincher Februrary-related than Social Network-related and I'm sorry if you've discussed it already, I'm behind on my Boy Movie reading!, but what do you think about the role that adaptation plays in Fincher's work? I feel like you could almost track girl movie-ness to adapted-ness with GWtDT, Gone Girl, and Benjamin Button all being based on written fiction (arguably more adaptation-y than his based-on-people movies), and in the case of GWtDT, having the Swedish movie version out a couple years ahead. Fight Club is also based on a book and is obv *the* boy movie, but I'd sort of argue that some of that is an audience issue. I think as a book at least, it's sort of a homoerotic misandrist text, like the Social Network seems to be in some ways. I'm not saying there's anything there and I'm not sure what it would be, I just wanted to know what you thought.

Also, the graphics here? Perfect. Whoever does them is clearly one of the best in the game.

Also want to applaud you for your guerilla marketing the past week or so!! Made me chuckle every time